|

Energy forecasters believe natural gas demand at or beyond 30 quads can be satisfied with only modest price increases. Among the organizations that estimate long-range natural gas and other energy prices are the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), the American Gas Association (AGA), the Gas Research Institute (GRI) and the National Petroleum Council (NPC). The gas consumption forecast of each of these organizations exceeds 30 quads per year by 2015, and none differs by more than 10 percent from the accelerated projection level of 32.6 quads.

Wellhead gas prices, which hover in the $2 per million Btu (MMBtu) range today, are projected by three of the four organizations to increase modestly in real terms by 2015, ranging from $2.29 to $2.63. (NPC does not include a specific price estimate for 2015; its estimate for 2010 is $2.95. NPC's price estimate is discussed below.)

Each of the forecasts projects that prices to the ultimate consumer will increase less than the wellhead price. That is, efficiency improvements in gas transmission and distribution will continue to offset some of the higher costs of gas exploration and production. There is also uniform agreement among the forecasts that prices to the largest-volume customers — electric utility plants — will increase more than the prices to residential, commercial and industrial customers. In fact, residential and commercial prices are shown to remain unchanged or to decline in real terms in most of the forecasts, despite the higher price of gas at the wellhead.

Washington Policy and Analysis believes that the demand levels of the accelerated projection can be satisfied with wellhead prices in the mid-$2 per MMBtu range (real dollars, adjusted for inflation) in 2015. Residential, commercial and industrial prices should be relatively constant in real terms with prices for central-station electricity generation somewhat higher.

Continued resource base expansion

and technological improvements will ensure long-term price stability. Long-term price projections for natural gas have customarily resembled a "hockey stick." They tend to rise very modestly in the short- to mid-term, but at some point they turn sharply upward. One of the primary reasons for this pattern is that forecasters tend to take an engineering approach to quantifying the gas resource base. They assume that their initial estimate of the resource base is accurate, and therefore, over time, this resource base will decline, pushing prices up. In fact, all estimates of the gas resource base performed over time by the same estimators and using the same methods have increased, often dramatically.

and technological improvements will ensure long-term price stability. Long-term price projections for natural gas have customarily resembled a "hockey stick." They tend to rise very modestly in the short- to mid-term, but at some point they turn sharply upward. One of the primary reasons for this pattern is that forecasters tend to take an engineering approach to quantifying the gas resource base. They assume that their initial estimate of the resource base is accurate, and therefore, over time, this resource base will decline, pushing prices up. In fact, all estimates of the gas resource base performed over time by the same estimators and using the same methods have increased, often dramatically.

Resource base estimates tend to heavily influence price forecasts. For example, NPC's recently released work indicates that if its resource base estimate were increased by .260 quads, the 2010 gas price estimate would decline by $0.93 per MMBtu — a reduction of roughly one-third. Interestingly, NPC's 1999 resource base estimate was 176 quads greater than its 1992 estimate, and 304 quads greater when taking into account the 128 quads produced since the 1992 estimate was made.

Additionally, forecasters have historically underestimated the impact of new technologies on gas exploration, production, delivery and use. There is an inherent tendency of forecasters to assume that the most recent round of invention and innovation will be the last for a while. That is, the technological leap of the computer is viewed as an endpoint rather than as a starting point. Again, underestimating technological progress affects price. NPC estimates that if it had employed a higher rate of technological improvement for gas production the 2010 gas price estimate would be reduced by $0.32-about 10 percent. In this analysis it is not assumed that the resource base expansion and technological progress experienced in recent years is an anomaly.

In the deregulated era, natural

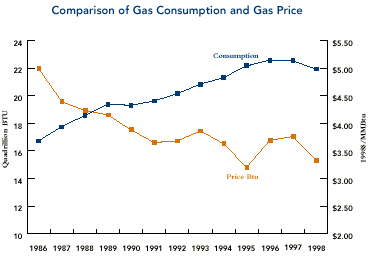

gas prices have fallen significantly. The natural gas industry has undergone a lengthy process of deregulation, and, as a result, natural gas prices have fallen significantly in real terms (adjusted for inflation). That is, gas prices have gone up far less than the gross domestic product (GDP) index that includes a bundle of goods and services purchased by consumers. For example, from 1987 through 1998 the GDP index increased by 36 percent while the price of gas increased by only 3 percent. All gas consumers, regardless of size or class of service, enjoyed significant real price declines over this period. The declining cost of the commodity, when coupled with higher-efficiency equipment that requires less gas to operate, is doubly beneficial for consumers.

gas prices have fallen significantly. The natural gas industry has undergone a lengthy process of deregulation, and, as a result, natural gas prices have fallen significantly in real terms (adjusted for inflation). That is, gas prices have gone up far less than the gross domestic product (GDP) index that includes a bundle of goods and services purchased by consumers. For example, from 1987 through 1998 the GDP index increased by 36 percent while the price of gas increased by only 3 percent. All gas consumers, regardless of size or class of service, enjoyed significant real price declines over this period. The declining cost of the commodity, when coupled with higher-efficiency equipment that requires less gas to operate, is doubly beneficial for consumers.

While wellhead prices may exhibit short-term volatility, efficiency gains in transmission and distribution continue to exert steadily downward price pressure. While the price of gas at the wellhead can

exhibit significant volatility in the short run, moving up or down based on changing weather or various market factors, gas consumers are largely insulated from these movements for a number of reasons. The consumer's bill has two primary components: the cost of the gas commodity and the cost of delivering the commodity. Gas pipelines and local gas utilities have become increasingly efficient in the delivery process, and the real price of the delivery component fell by about 35 percent from 1987 through 1998.

exhibit significant volatility in the short run, moving up or down based on changing weather or various market factors, gas consumers are largely insulated from these movements for a number of reasons. The consumer's bill has two primary components: the cost of the gas commodity and the cost of delivering the commodity. Gas pipelines and local gas utilities have become increasingly efficient in the delivery process, and the real price of the delivery component fell by about 35 percent from 1987 through 1998.

(Obviously, this trend cannot continue indefinitely.) The wellhead cost of gas also declined over this timeframe — by more than 13 percent — although the movement in wellhead prices was more erratic and less pronounced than the transmission and delivery charge.

(Obviously, this trend cannot continue indefinitely.) The wellhead cost of gas also declined over this timeframe — by more than 13 percent — although the movement in wellhead prices was more erratic and less pronounced than the transmission and delivery charge.

Consumers also are insulated because gas suppliers generally hold a mixed portfolio of gas supplies, including gas from various long-term and short-term contracts. They can purchase gas when market conditions are favorable and store this gas until needed. The free market for gas is still in its infancy, and as we move forward through the forecast period the array of available new technologies and market strategies that can ultimately lower prices will continue to expand.

Natural gas competes primarily with electricity, oil and coal, all of which are expected to have relatively flat or declining real prices throughout the forecast period. Natural gas is not sold in a market vacuum. It competes with a variety of other energy forms — primarily with electricity, oil and propane in the residential and commercial markets; with oil, electricity and coal in the industrial market; and with oil, coal, nuclear energy and various renewables in the market for electricity generation. Over the forecast period, electricity markets will be deregulated, the oil market will become increasingly a world market, coal and nuclear will fight to retain their dominance in generating electricity, and renewable energy forms will become more competitive. The market for energy will be a market of increased competition and innovation with prices that decline or rise very modestly in real terms.

New gas applications can help level the load of gas suppliers. One positive aspect of some of the new gas technologies included in the accelerated projection, such as gas cooling and distributed generation, is that they can help level gas demand. The extreme demand peaks and valleys caused by the need for space heating can be smoothed, allowing for more efficient (i.e., less costly) use of the delivery system.

Back to Table of Contents

|

Having It Your Way: Customer Choice

More than three-fourths of the natural gas market has been opened to competition. In the past, natural gas was sold from gas producers to long-distance gas pipeline companies, who sold this gas to utilities, who sold this gas to the ultimate consumer.

This process began to change in the 1980s when large-volume gas customers — industrial facilities and electric utility plants — began to purchase gas directly from producers or from gas marketers. The gas delivery process was unchanged-pipelines and utilities still delivered gas to the customer, but they did not buy and sell the gas commodity. "Customer choice" in the gas industry, as in the telephone industry before it, was seen as a means to put downward pressure on prices while offering new services to customers through increased competition

This opportunity for customer choice has expanded dramatically, and the move is now prevalent in commercial and residential markets as well. In fact, customer choice is now available to two-thirds of the commercial market and 44 percent of the residential market — and growing.

|