|

What is a fuel cell?

A fuel cell is similar to a battery, using an electrochemical process rather than combustion to directly convert chemical energy into electricity and hot water. The chemical energy typically comes from the hydrogen contained in natural gas. Because fuel cells do not burn gas, they operate virtually pollution-free. And unlike a battery, a fuel cell doesn�t run down or require recharging; it will produce electricity

and heat, quietly and cleanly, as long as fuel is supplied.

and heat, quietly and cleanly, as long as fuel is supplied.

Fuel cells offer high-energy efficiency � high-energy output per unit of energy input:

- Fuel cells produce electricity at efficiencies of 40%-60% or more, compared with 30%-34% for conventional boilers.

- When the fuel cell�s heat and electricity can both be used, efficiency levels can exceed 80%.

- Because fuel cells operate at the user�s site, they don�t suffer the typical 8% loss of energy of electricity through conventional distribution lines.

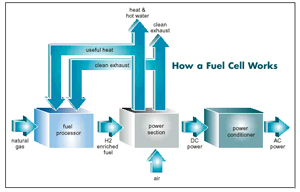

A fuel cell has

three basic components: the fuel processor, which combines the gas with steam generated by the system to produce a hydrogen-rich fuel mixture; the power section, which combines the fuel mix with oxygen to produce electricity; and the power conditioner, which converts the resulting direct current power to alternating current. The byproducts of the process, water and heat, can be used for other operations.

three basic components: the fuel processor, which combines the gas with steam generated by the system to produce a hydrogen-rich fuel mixture; the power section, which combines the fuel mix with oxygen to produce electricity; and the power conditioner, which converts the resulting direct current power to alternating current. The byproducts of the process, water and heat, can be used for other operations.

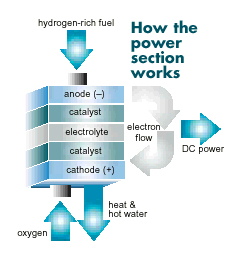

Within the power section of the fuel cell,

the hydrogen mix is fed into a negative electrode (anode), and oxygen is fed into a positive electrode (cathode). These electrodes are separated by an electrolyte. Encouraged by a catalyst, the hydrogen atoms split into protons and electrons. The protons move through the electrolyte to combine with the oxygen in the cathode. The electrons flow through a separate electrical cir-cuit to create direct current before they rejoin the hydrogen and oxygen in the cathode to form molecules of water. useful heat clean exhaust fuel processor power section power conditioner natural gas H2 enriched fuel DC power AC power heat & hot water clean exhaust air hydrogen-rich fuel oxygen anode (�) catalyst catalyst electrolyte cathode (+) electron flow heat & hot water DC power How a Fuel Cell Works How the power section works.

the hydrogen mix is fed into a negative electrode (anode), and oxygen is fed into a positive electrode (cathode). These electrodes are separated by an electrolyte. Encouraged by a catalyst, the hydrogen atoms split into protons and electrons. The protons move through the electrolyte to combine with the oxygen in the cathode. The electrons flow through a separate electrical cir-cuit to create direct current before they rejoin the hydrogen and oxygen in the cathode to form molecules of water. useful heat clean exhaust fuel processor power section power conditioner natural gas H2 enriched fuel DC power AC power heat & hot water clean exhaust air hydrogen-rich fuel oxygen anode (�) catalyst catalyst electrolyte cathode (+) electron flow heat & hot water DC power How a Fuel Cell Works How the power section works.

Fuel Cell Developments and Case Studies

A new 48-story sky-scraper at 4 Times Square in New York City, publicized for adopting high energy-efficiency and indoor-air quality standards, uses two fuel cells to generate enough electricity for the building�s nighttime base load power needs and 4% of its daytime power needs.

In June 1999, First National Bank of Omaha, Neb., began using four PAFC fuel cells to run its new Technology Center, which houses computers and data processing. The system boasts down time of only .31 to 3.18 seconds per year, compared with 63 minutes of down time for a conventional �uninterruptible� system.

South County Hospital in Wakefield, Conn., recently installed a PAFC fuel cell to provide base load electricity and thermal energy for space heating. In the event of a power outage, the fuel cell will automatically run as an independent system to power the hospital�s critical loads. In addition, the hospital will reduce its energy costs as well as the amount of polluting emissions generated.

NiSource subsidiary EnergyUSA and the Institute of Gas Technology have teamed up to field test several residential and small commercial- sized fuel cells in 2000, expecting to have units available to consumers by year-end.

New Jersey Natural and GE Fuel Cells have reached an agreement naming the utility to begin marketing residential fuel cells in 2001. GE Fuel Cells is a joint venture between GE Power Systems and Plug Power.

In July 1998, a single-family home in Latham, N.Y., was discon-nected from its local electric utility and pow-ered up with a 7 kW residential PEM fuel cell from Plug Power LLC � the first house ever to do so. In August 1999, the system was convert-ed to use the home�s incoming natural gas line as the fuel supply, with expected expenses of about 7 cents per kW.

ONSI Corp.�s fleet of PAFC fuel cells has logged in more than 3 million hours of in-ser-vice operation since 1992. The company now has 170 units operating in 25 North American states and provinces, and 12 other countries. The longest-running unit has surpassed 43,000 hours, and a unit in Tokyo, Japan, ran for a record 9,500 continuous hours before being shut down for scheduled maintenance.

For more information:

To learn more about how fuel cells, and other new technologies, can help fuel the future using natural gas, visit www.fuelingthefuture.org. Other fuel cell contacts are:

Back to Table of Contents

|

Environmental Benefits of Natural Gas Fuel Cells

The U.S. Energy Information Administration ranks natural gas fuel cells as the cleanest form of fossil fuel-based electricity generation. Here are some reasons why:

A 70% reduction in carbon dioxide (a greenhouse gas) emissions compared with a new coal-fired power plant, and a 23% reduction over a conventional natural gas-powered combined-cycle plant.

A reduction in nitrogen oxide (the primary contributor to ozone or smog) emissions that is 85% less than the ultra-tight limits set in the Los Angeles area.

Virtual elimination of sulfur dioxide (the primary contributor to acid rain) emissions and particulate matter.

No solid waste discharges or negative impact on surrounding water quality, and no water consumption.

Types of fuel cells

Several types of fuel cells have been developed, distinguished by the type of electrolyte they use:

Phosphoric acid (PAFC)

PAFCs are the most commercially developed and already are in use in hospitals, nursing homes, hotels, offices, schools and an air-port terminal. They also could be used in large vehicles such as buses and locomotives. PAFCs generate electricity at more than 40% efficiency, compared with 30% for the most efficient internal combustion engine.

Proton exchange membrane (PEM)

PEMs operate at relatively low tempera-tures and can vary their output quickly to meet shifts in power demand. Because they also can be made smaller and lighter than other fuel cells, PEMs are suited for automobiles, small buildings or even replacements for rechargeable batteries in video cameras.

Molten carbonate (MCFC)

Operating at high temperatures -about 1,200 degrees F - MCFCs potentially could produce higher-temperature byproduct heat.

Solid oxide (SOFC)

Typically using a hard ceramic material instead of a liquid electrolyte, SOFCs also operate at high temperatures - up to 1,800 degrees F. Suited for big, high-power applications such as industrial and large-scale central electricity-generating stations.

Alkaline

Long used by NASA on space missions, these cells can achieve power generat-ing efficiencies of up to 70%. Until recently they were too costly for commercial applications, but sev-eral companies are examining ways to reduce costs and improve operating flexibility.

Others

Directmethanol fuel cells are relatively new and similar to PEMs except that the anode catalyst itself draws the hydrogen from the liquid methanol, eliminating the need for a fuel reformer.

Regenerative fuel cells

also are fairly new and are promising for closed-loop forms of power generation.

|